We all experience stress, right? But does the kind of person we are have an impact on how we experience that stress? McCrae & Costa (1987) originally defined 5 personality dimensions on which every individual’s personality can be measured via the NEO-PI-R test: OPENNESS, CONSCIENTIOUSNESS, EXTROVERSION, AGREEABLENESS and NEUROTICISM. The type of personality we inhabit […]

Developmental

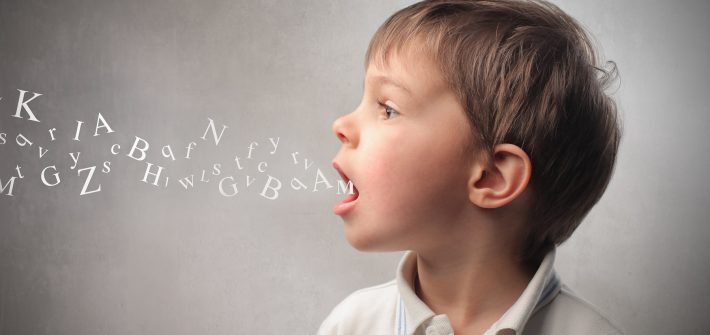

The language of growing up

Developmental psychologists study how we grow and develop throughout our lives; and it is the application of this information which can benefit society by helping ensure that we fulfil our developmental potential. It is a diverse topic, and so this post focuses only on the benefits it has brought through its discoveries within the field of […]